The place where the Forrest Hall stranded has always been regarded as a “murder’ scene. Today, the blurred remains of the once proud sailing ship can be glimpsed in favourable conditions.

Salvage Attempt at Forrest Hall Wreck (teara.govt.nz)

Salvage Attempt at Forrest Hall Wreck (teara.govt.nz)

The New Zealand coastline is peppered with hundreds of shipwrecks. Skeletons of small fishing boats, along with sizeable passenger liners such as the Mikhail Lermontov, lie rotting in the elements. Some are well known. The Rainbow Warrior, Wairarapa and Elingamite continue to fascinate those interested in things nautical. The General Grant, although not a New Zealand coastal wreck, but classed as a New Zealand wreck because she met her end in the Auckland Islands, still holds the promise of vast riches. Some of these once splendid vessels are now destinations for divers. Most however, are surrounded by dangerous seas and perilous tidal rips and are only visited by the marine life which team around them in the murky depths. It is not known how many wrecks are buried deep in the sand and have subsequently been lost to us. Occasionally, a freak combination of tide and shifting sand will reveal, for a tantalizingly short time, the twisted remains of a forgotten ship.

EARLY SHIPWRECKS

The first recorded New Zealand shipwreck was that of the 800 ton Endeavour. She lies on the bottom of Fasile Harbour in Dusky Sound where she sank in October 1795 with a cargo of cattle and grain. A number of stowaways, including a woman, boarded her in Sydney for the voyage to Dusky Sound. Fortunately, they survived the sinking. The fate of the poor cattle is unknown.

The worst shipwreck on the New Zealand coast, in terms of fatalities was the loss of H.M.S Orpheus. The warship broke up at the entrance to the Manaku Harbour in 1863 with the tragic loss of 189 sailors who were on their way to support the British settlers during the Maori War of that year. In the days of sail, sailors relied on their eyesight to navigate around a coastline. Most mishaps occurred in bad visibility. Fog and storms were responsible for the vast majority of wrecks. Along with the treacherous weather, uncharted rocks were a constant menace to all who sailed the southern oceans in the 18th and 19th centuries.

THE FORREST HALL MISHAP

The loss of the Forrest Hall was quite different from all other local marine mishaps. It’s the only known occasion of a ship on the New Zealand coast to be completely wrecked in fine weather.

February 27th 1909 began a fine, clear day. A light breeze was propelling the 26 year old 2000 ton iron hulled sailing ship towards her destination of Antofagasta in Chile. Three weeks earlier, she had loaded 3,500 tons of coal in Newcastle, Australia. At 9.30 that morning, with all sails fully set to avail of the favourable conditions, the ship slammed onto Ninety Mile Beach, 25 miles south of Cape Maria Van Diemen. Everyone onboard managed to clamber ashore. They salvaged as much as they could before their ship started to list badly. High tide smashed into the stricken ship with waves reaching half way up the masts. The pounding caused the ship to break apart. The crew watched in horror as their beautiful ship disintegrated into a total wreck. The exhausted men then began what must have been a rather hazardous trek south to civilization and assistance.

Wreckage from Forrest Hall (louisalifeboat.weebly.com)

Wreckage from Forrest Hall (louisalifeboat.weebly.com)

The inquiry, held three weeks later in Auckland placed the blame for the disaster on the shoulders of Captain Collins. His navigation was badly out. The ship’s course had been set to sail through Cook Strait or even pass New Zealand to the very south of the country. Despite the sighting of land, estimated to be 15 miles away, the captain refused to alter course. The Forrest Hall continued to sail directly towards the coast. Oddly, Collins also refused to take soundings to ascertain the water’s depth. The Chief Officer continued to urge his captain to change course, but for some unexplained reason, his protestations were ignored. Only three miles from the beach, but too late to avoid disaster in a large, fully laden ship slow to respond to direction changes, the Chief Officer tried to alter course. The enquiry exonerated him of all blame while the captain lost his master’s certificate for two years.

It will never be known why Captain Collins blatantly ignored the safety procedures he should have employed while his ship was under full sail and within the sight of land. He had suffered a series of epileptic fits since commencing the voyage, so his state of health may partly explain his actions. There was also talk of drunkenness among the crew and the captain was seen to be intoxicated a few hours before the stranding of his ship. As a result of the Forrest Hall’s loss, some shipping companies took closer looks at the competence and health of the men they commissioned to master their ships.

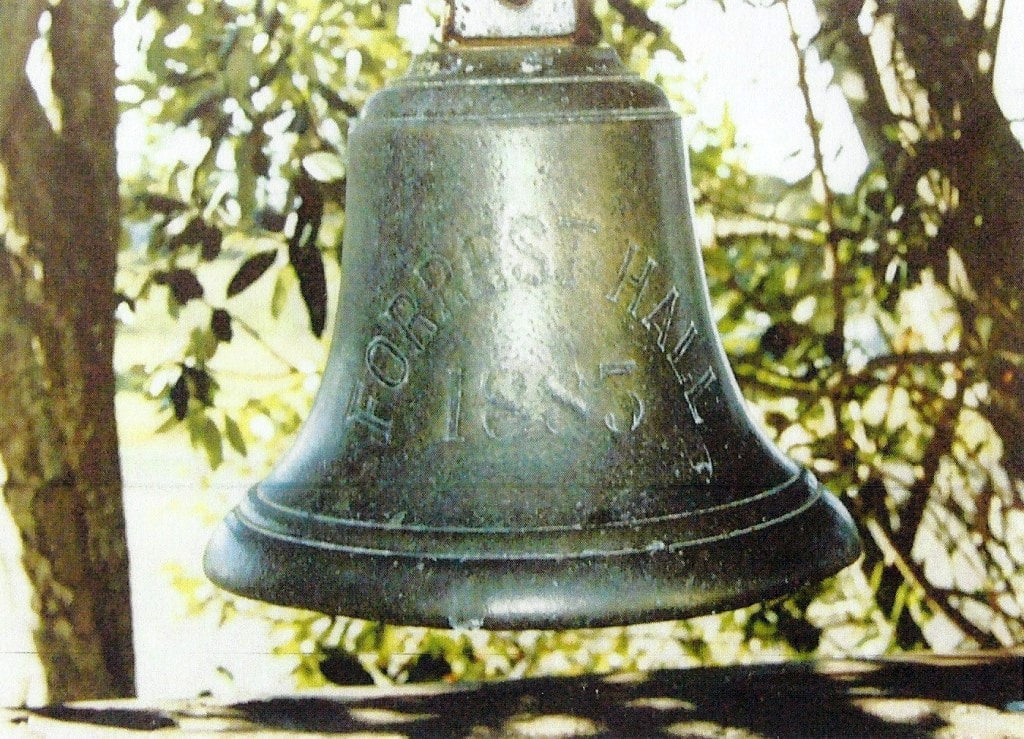

After all the crew had made it to the shore, Captain Collins and his first mate went in search of a village to raise the alarm. They found Te Hapua on the far shore of Parengarenga Harbour where the Maoris living there looked after the beleaguered crew. To show gratitude for their kindness, Captain Collins presented them with the ship’s bell. It was later donated to Te Hapau School where it proudly hangs in the school’s grounds.

The ship’s figurehead was for some strange reason buried in the sand by a local a short time after the event. It is thought to still be there because the guy forgot where he buried it!.

Ceidrik Heward

Visit Today : 707

Visit Today : 707 Total Visit : 1078322

Total Visit : 1078322