The vast majority of New Zealanders have never heard of the Cospatrick yet it remains New Zealand’s worst maritime disaster.

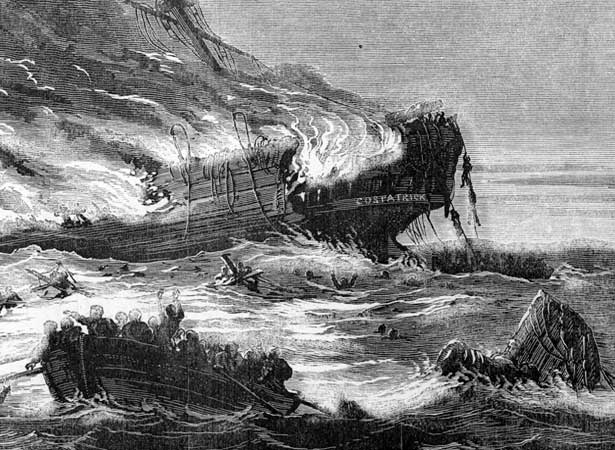

The fire that engulfed the immigrant ship Cospatrick is one of the 19th century’s most horrendous tragedies and is the stuff nightmares are made of.

In the late 1800s, New Zealand was a popular destination for British citizens wanting to escape the harsh conditions they were experiencing at the time. Gold was being discovered at a number of places around the young colony and it seemed the perfect time to make the move across the world to a new life. Hundreds of ships made the 3 to 4 month voyage and most arrived without incident.

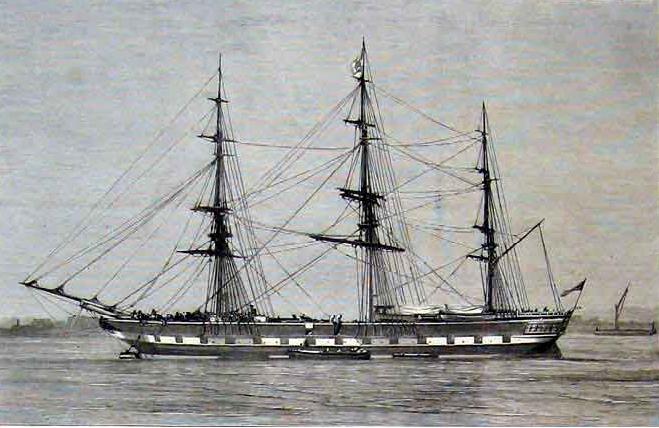

Launched in 1856, the 1,199 ton wooden Blackwall frigate Cospatrick spent her early career trading between England and India. In 1873, the ship was sold to Shaw, Saville & Company to carry cargo and passengers from England to New Zealand. This type of vessel was regarded as safe and comfortable and between 1830 and 1875, 120 of them were built.

FATEFUL VOYAGE

The Cospatrick left Gravesend for the long voyage to Auckland on 11 September 1874. Reports vary but most say there were 433 assisted passengers including 125 women and 126 children onboard. The males were mostly farm hands from Oxfordshire. The crew numbered 44 men under Captain Alexander Elmslie. As was common with immigrant voyages back then, eight infants died and one was born in the confined, claustrophobic quarters onboard.

The ship’s cargo included railway irons, cement powder, oils, varnishes, turpentine, rum, brandy, wine, beer, along with the personal belongings of the many passengers. Although it was against shipping regulations to carry such flammable cargo on a passenger ship, authorities agreed to the goods as long as strict fire restrictions were followed. There was to be no smoking inside the ship, galley cooking fires had to be doused by 7pm and no unauthorised lamps or candles were allowed to be lit. For added security, night patrols were carried out by volunteer passengers.

DISASTER

Two months passed and all went well until the 17th November when a still born baby was delivered. It was a bad omen for what was to follow a few hours later. Just after midnight that day, the Cospatrick was sailing roughly 400 miles (640km) south of the Cape of Good Hope when fire broke out deep in the forward hold. The ship’s second mate, Henry Macdonald, later said he was awoken by a cry of “Fire!” He raced to the front of the ship to find a fire had broken out where paint and ropes were stored. The sleeping passengers were soon awoken by the frantic shouting from the crew and they quickly realized the peril they were in. Fire at sea in the days of wooden sailing ships, with flammable bitumen used to waterproof the decking along the length of the vessel, was the worst nightmare of all. The crew attempted to douse the flames with inefficient fire hoses while the Captain tried, but failed, to turn the Cospatrick before the wind to take the smoke and flames forward of his ship. As the wind quickly blew the flames the length of the doomed vessel, the terrified passengers fought to clamber into lifeboats at the stern but many were killed when the three masts crashed onto the decks.

Cospatrick Disaster (NZ History)

Cospatrick Disaster (NZ History)

There were only 5 lifeboats capable of carrying 190 people, meaning 287 passengers on this voyage had no means of escaping. In the panic to flee the flames only 3 lifeboats managed to be launched. Sadly, the first one holding about 80 women (more than double the lifeboat’s capacity) capsized as it hit the water and since the women were dressed in thick, ankle length Victorian bed wear, all of them quickly drowned. Thirty nine year old Captain Elmslie threw his wife overboard then followed her. At the same time the ship’s doctor, Dr Cadle, jumped with the captain’s little boy in his arms. All were drowned. Only 62 people in the remaining 2 lifeboats managed to successfully clear the burning ship. They watched in horror as the fierce flames burnt alive those remaining on board.

The burnt out hulk, that had been their home for the previous two months, drifted for 48 hours before sinking. The two lifeboats with now 30 traumatized passengers in each, stayed together until the night of 21 November, when they were separated during a storm. One of them was never seen again.

EXTREME SUFFERING

As the days dragged on the number of survivors in the remaining boat dwindled. A sail was rigged on a pole using the petticoat of a young girl who had died. The few men who managed to stay alive endured the torture of drifting without food, fresh water, or warmth, in the middle of nowhere. Some died of injuries and hypothermia. Others succumbed too quickly to the temptation of drinking saltwater. Some went mad and leapt overboard.

After drifting for 10 days, only five men were still alive after drinking the blood and eating the livers of their dead companions. They were picked up by a cargo ship, British Sceptre. They had drifted about 500 miles (800 km) north-east from where Cospatrick had sunk. Sadly after such unimaginable suffering, two of these men died shortly after being rescued. The three survivors were later able to provide most of the evidence for the maritime inquiry. The cause of fire was put down to someone trying to raid the kegs of spirits in the boatswain’s store stupidly using a naked flame to see their way, although another possibility was spontaneous combustion from a combination of oils, paints, rags and coal dust deep in the hold.

The lack of lifeboats and the inability to launch them successfully at sea caused public outrage, but ships continued to set sail with not enough lifeboats to save all onboard for another 38 years. It would take the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, with its woeful lack of lifeboats, to force the passing of an international law making it compulsory for all vessels to carry enough lifeboats to accommodate everyone.

The above engraving of the Cospatrick’s three survivors, and the engraving of Captain Elmslie and his wife and child, were both published in the Illustrated London News in 1875. This was the world’s first fully illustrated newspaper and reporting on dramatic events, especially when tragedy was involved, was good for sales. The horrific sinking of the Cospatrick with the loss of 474 lives was one of the most talked about disasters of that year in both Britain and New Zealand.

IMPACT ON THE SURVIVORS

The three surviving crew members, Henry McDonald, Thomas Lewis, and young seaman Edward Cotter, were taken to St Helena for hospital treatment, before being returned to London. Their story caused a sensation in British newspapers and the pressure from the media took its toll on the men. For a while, immigration numbers to New Zealand dried up. Thomas Lewis never ventured far from his home and died in his village in 1894. Edward Cotter went on the road in a music hall show and briefly enjoyed celebrity status. It was a time when Victorians were fascination with shipwreck survivors and cannibalism. Although he became an alcoholic, he managed to live to 84. Henry McDonald was the saddest of the three Cospatrick survivors. He became somewhat violent before he went insane. He died in the Dundee Royal Lunatic Asylum a little more than 10 years after being rescued.

Although the ship was British and none of her passengers ever set foot on New Zealand soil, the fact they planned to settle here and become New Zealanders, has made the loss of the Cospatrick a New Zealand story and as a result the tragic loss is classed as this country’s worst sea disaster.

Ceidrik Heward

Visit Today : 161

Visit Today : 161 Total Visit : 1072102

Total Visit : 1072102