During the various gold rushes around New Zealand in the latter decades of the 19th century, a number of towns flourished to provide provisions and services to the miners who set them up. A small number have survived to the present day but the majority have disappeared into the mist of history. It is estimated there are 70 ghost towns on the West Coast alone. However, although they no longer exist, there are poignant reminders that once people lived and died in these forgotten towns.

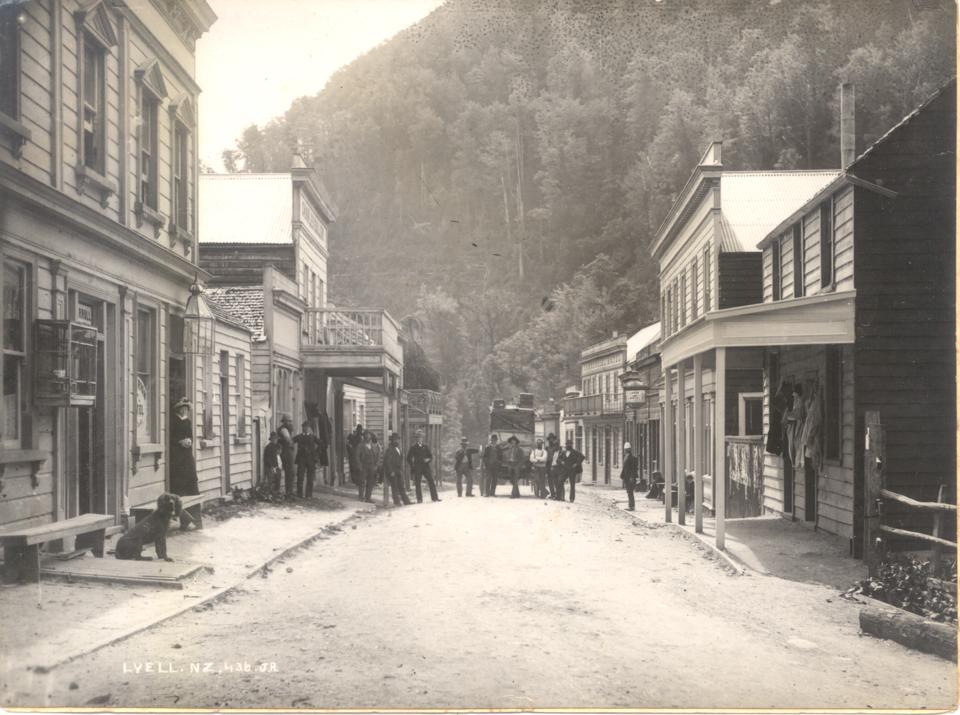

LYELL

In 1862, a pair of Maori prospectors found gold in Lyell Creek on the West Coast of the South Island but kept their find to themselves. Six years later, two Italian miners found gold in quartz veins on the banks of the same creek. This resulted in some of the richest discoveries in New Zealand mining history.

Despite being built on a steep hillside in a damp, dark ravine in the Buller Gorge, the town of Lyell grew rapidly to meet the demands of the miners who flocked to the area. Between 1880 and 1896, the town was at its peak with a population over 2000. There were six hotels, three stores, one drapery and ironmonger store, three butchers, one baker, two bootmakers, two agency offices, a blacksmith shop and a school. Remarkably, four newspapers were also published during the life of the town.

TRANSPORT PROBLEMS

Lyell was known to be the most inaccessible goldfield in New Zealand. Transport to and from the town was treacherous as the Buller River was the main access to the outside world. Only Maori canoeists were strong enough to paddle against the powerful rapids. William Stuart, one of the first residents of Lyell, wrote about his journey up the Buller river in his journal: ‘canoes are poled and paddled, towed by ropes then pulled by all hands until they finally reached their destination’. Early horse tracks were rough and unstable for carts, so in 1870 a road called Cliff Street was created. This became the main, and only, street of Lyell. In 1877, a road was formed along the Buller River, which made travelling to the isolated gold town a little safer. This development allowed women and children to venture into Lyell and was the catalyst for the development of a community in the town.

DAILY LIFE

Miners moved from the riverside tents into the single and double storied wooden buildings that were built to form Lyell village. As children were born or were brought there by canoe, the demand for adequate education rose. The journey down river to the school at Westport was a dangerous and exhausting endeavour, so in 1874, Lyell residents erected their own school to educate their children. A small farm across the Buller River supplied much of the town with milk and vegetables which were transported in a box that was propelled across the river by pulling on ropes. This device also enabled the residents to cross the Buller River, although there were often complications resulting in death. By the 1880s, contact with neighbouring communities began with a regular coach travelling from Lyell to Nelson.

Disaster struck in 1896 when the town’s water supply failed. Fire broke out and eighteen of Lyell’s wooden buildings burned down. These included the National Bank, three hotels, several stores as well as residents’ houses. Only a few businesses were rebuilt as by then the easy gold had been won and the town’s inhabitants began to move away in search of new opportunities. By 1901, only 90 people remained in the once bustling town. In 1913, the last mine closed but a few people stayed on in the hope of finding new gold. However, in 1963, the town’s fate was sealed when the last functioning building, the Post Office Hotel, burned down and Lyall faded into history. The remains of this West coast gold town were left to the rain and wind that frequently lash this part of New Zealand. Lyall had officially ceased to exist.

The location where the town once stood is now a campsite and a track leads to the cemetery and the remains of a stamping battery. A dray road built during the gold rush is now the start of the aptly named Old Ghost Road, a walking and cycling track that snakes for 85km (53miles) through the challenging West Coast landscape.

MACETOWN

In recent years the ghost settlement of Macetown has been put on the tourist map. This was another isolated town created by gold miners who suffered the freezing winters and hot summer temperatures to search for gold. The original bakehouse and a beautiful little stone dwelling known as Needham’s Cottage have been rebuilt and now make the rather exciting trip from Arrowtown worthwhile. A wooden stamping battery and some other mining equipment have been partially repaired and can be seen in situ. To make the journey from Arrowtown to Macetown requires crossing the Arrow River 22 times as it flows through the valley separating the two towns. By crossing, I mean through the water, as there are no bridges.

INTERESTING HISTORY

Macetown was established on a river terrace on the Arrow River upstream from Arrowtown after gold was found there in late 1862. It was one of the remotest gold towns ever created in New Zealand. It is commonly recounted that the Mace brothers working up the Arrow River and the Beale brothers working over the hills at Skippers converged on the spot almost simultaneously. In January 1863 miners from the heavily worked Shotover and Arrow goldfields moved into the area, and a settlement was soon established with alluvial mining in the river and stream beds as its economic base. The higher river terraces were also worked once races were constructed to bring water to the claims. Macetown was initially named ‘the Twelve Mile’, this being the estimated distance of the location from Arrowtown. It’s actually 9 miles (14.5km) The inhabitants had to contend with the intense cold of the freezing winters, along with loneliness caused by the isolation, and if any of them needed medical treatment, it involved the long, uncomfortable trek to Arrowtown. In fact, Macetown was so remote that during the winter months of 1862 to 1900 when the town was at its peak, with two hotels, two bakeries, a drapery store and post office, many of the females, unable to handle the freezing weather in their draughty houses, moved to Arrowtown leaving the men alone to look after their claims.

RAPID DECLINE TO GHOST TOWN

The winter snows and frozen water supplies, along with flooding in the gullies and challenging access which increased costs, were not the only reasons for the failure of most of the Macetown mines. Mismanagement and misrepresentation of claims to attract capital also took their toll. The erection of the massive Homeward Bound Battery in 1910 was followed by the brief resurgence of government-sponsored mining during the 1930s depression. However, by this time, it was obvious to everyone that the gold was finally mined out. As mining was the single economic base, the township did not long survive the closure of the mines. Many buildings that survived until the end of the Second World War were removed and used elsewhere. In 1947, the first hanger for Southern Scenic Airways at Queenstown airport was built of Macetown iron. The area where this fascinating little gold town once occupied was gazetted as an historic reserve in 1980.

MEMORIES OF MACETOWN

When I visited the area a number of years ago, trees planted by the inhabitants in the 1860s grew rather forlornly in the centre of the dry yellow valley. I felt if I turned around, I’d see a child run up to me wanting to play. In fact, the last inhabitant left Macetown in 1930. It is still one of the most isolated places in New Zealand, but it is this isolation that is its attraction. In the past decade with a growing interest in New Zealand’s history, around 8000 people each year make the effort to experience the special magic that fills the air in this little Central Otago valley. Macetown truly is one of New Zealand’s most melancholic ghost towns.

Ceidrik Heward

Ceidrik Heward is an Amazon TOP SELLING AUTHOR and has lived and worked in 7 countries working as a TV cameraman, director and film tutor. For the past 17 years he has focused on writing and has been published in magazines and newspapers in Europe, USA, Asia and the Middle East.

His interests include photography, psychology and metaphysics. He loves to read and always has at least 3 books on the go. He has written 22 manuals/books and has just completed his 4th short novel. Ceidrik believes sharing information and stories is the best way to stimulate the imagination and enrich our lives.

Visit Today : 204

Visit Today : 204 Total Visit : 1133381

Total Visit : 1133381

Speak Your Mind